Tea Bendix breaks with the convention of text as something primarily linked to the written word in her works. They make the reader aware that also sound, picture, and gesture can be part of a story. This is how her works come to appear as a peculiar kind of multimedia-performance in book form.

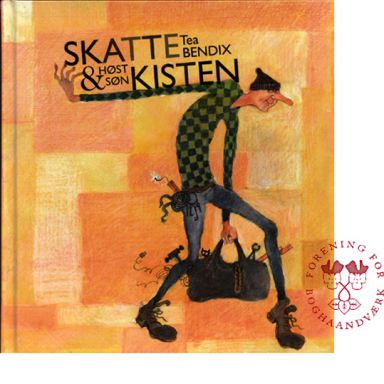

Tea Bendix has both written the text and drawn the illustrations in her two publications to date. In her 1997 début, Skattekisten (The Treasure Chest), a picturebook, we hear about a tall lanky thief with a glint in his eye, who gets caught redhanded by the bank manager in the act of breaking open a safe. But when the thief tells of his treasures – including a kitten that had been his grandfather’s, and a candle from a birthday cake – the bank manager swaps a bar of gold for the treasure chest. The thief regrets this and gets his treasure back on promising to share it with the bank manager.

The story is simple,but draws attention to elements that are developed in Tea Bendix ensuing work as a writer and illustrator. The text only consists of comments said between the bank manager and the thief. The typography and graphic layout show the reader which words have to be stressed and intonated; thereby also becoming in part an aid to the correct musicality when reading aloud, and in part meticulously integrated into the visual expression. Then there is the precise portrayal of the characters’ facial expressions and gestures in the illustrations. The thief’s facial expressions alter slightly from sly through cunning, greedy, and disappointed to shrewd and finally cheerful. The characters’ gestures are depicted just as varied and precisely.

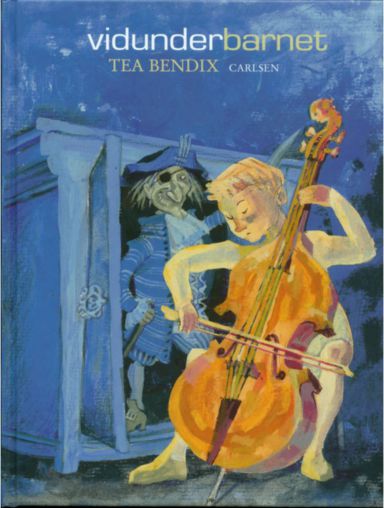

Tea Bendix | Vidunderbarnet, Carlsen 2001

One gets the same impression of a thoroughly composed unity from Tea Bendix’ novel Vidunderbarnet (The Child Prodigy, 2001). A headpiece begins every chapter that also contains a full-page black and white illustration. As in The Treasure Chest, the illustrations are first and foremost portraits of the characters in the book. These people are depicted with a sense of the wry, the humorous, and at times the grotesque.

The Child Prodigy is both a sad and cheerful story of how a child experiences the meeting of, on the one hand, the world of imagination and the senses and, on the other, the world of reality and physical order. The reader follows Gustav, a boy who not only has a lot of sensitivity but who is also talented both musically and at drawing, through the eyes of one of his friends. Tea Bendix suspends the sharp division between reality and imagination in her description of Gustav and his friends’ lives, letting the pirates that appear when Gustav plays his cello become a real living part of the children’s experience. But what is fun and laughter for the other children is deadly serious for Gustav. His mother and his teacher get worried when the fantasies he has through music go too far – the pirates have got to go, and Gustav is disciplined. Gustav’s joy of music takes a knock, but his technique is perfected. His teacher believes that now is the time to improvise. Gustav takes the plunge right at the end of the book during a big orchestral concert: playing with his demons, while at the same time taming them.

This story about artistic ambition, of living up to parental expectations, and of the often confusing relationship between make-believe and reality is written with the-child-as-reader in mind. Among other things, this is achieved by his friends observing Gustav, so that the events are registered through the senses of a child in a child’s words, and woven into the modern everyday life of school, football matches, and talk about spaceships and UFOs.

Furthermore, Tea Bendix writes about sound, music, dance, and the senses so that these appear alive to the reader. The writer creates sound images in the text. Language and sounds from people and pirates get the sounds of oboes, bassoons, a mouth organ and, of course, a cello mixed in with them. The children make, for example, a war cry: ”Take that, and that and that and that. That and that. That and that”, when fighting the pirates, and when Gustav stops before the concert his friends get him going again by clapping in time, expressed rhythmically in the text by using ”Four on the knee. Five under foot. Four on the knee. Five under foot”. The sound-picture culminates when Gustav has to take the plunge in a long formal iambic passage where Gustav’s play together with the orchestra is described using sentences such as ”Shall I chance it? Me, the great son of seventeen generations of robbers? Flee yourselves, you spineless cowards. Move! I’ll steer the ship.”

In this way Tea Bendix’ description of the especially-talented, peculiar child’s sensitivity and daring also becomes and image of the writer’s own unfurled talent in relation to writing for children.

written by Nina Christensen | translated by Ian Lukins